I WRITE this not as an adversary of public officials, but as a pastor concerned for the moral direction of our common life. The words “honorable legislator” are not empty courtesies. They carry with them a vocation: to serve the people through just laws, strong institutions, and fidelity to the Constitution. It is precisely because of this shared commitment to the common good that I feel compelled to speak plainly.

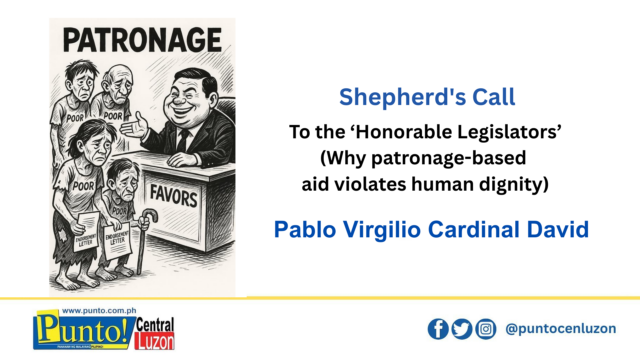

One of the quiet but grave moral failures of our public life is how easily we have normalized a system that forces the poor to beg for what they are already entitled to. When access to health care, education, or emergency assistance depends on a politician’s endorsement, a guarantee letter, or personal intervention, something deeply wrong has taken root—not only legally, but morally.

From a pastoral perspective, this is not a mere technical flaw in governance. It is a violation of human dignity.

Catholic social teaching is clear and consistent: the dignity of the human person does not depend on political favor. Health care, basic education, and social protection are not acts of generosity dispensed by the powerful; they are demands of justice owed to every person. When public assistance is delivered through patronage—through discretionary lump sums, lists controlled by politicians, and post-enactment intervention—it transforms rights into favors and citizens into supplicants. The poor are made to feel grateful not to institutions, but to individuals. This is not solidarity; it is dependency.

A concrete and troubling example lies in the recent decision of the bicameral conference committee to expand the Medical Assistance to Indigent and Financially Incapacitated Patients (MAIFIP) program—from ₱24.4 billion in the 2026 National Expenditure Program to ₱51.64 billion. On paper, MAIFIP sounds compassionate. In practice, it is nothing but a health pork barrel in the national budget.

Why? Because MAIFIP operates largely through a guarantee letter system, where access to medical assistance depends on securing a letter from a legislator. This effectively places politicians in control of who gets assistance, how much, and when. Health care is no longer delivered as a right flowing from need and citizenship, but as a favor mediated by political power—a classic system of patronage that turns illness into utang-na-loob.

Such systems are corrosive, not only to governance but to the moral fabric of society. They teach people, subtly but persistently, that survival depends on proximity to power. They replace trust in institutions with loyalty to patrons. They wound the dignity of the poor and, in the process, degrade public office itself. A society that normalizes begging as a pathway to public service slowly erodes its own moral foundations.

The problem here is not only pastoral; it is constitutional. The Supreme Court was unequivocal in striking down the pork barrel system: legislators may appropriate and oversee, but they may not intervene in the execution of the budget. Yet programs that rely on guarantee letters reproduce precisely what the Court prohibited. MAIFIP, as currently structured, is a lump-sum appropriation that requires post-enactment intervention by legislators to be accessed. When lawmakers decide beneficiaries and amounts, they are no longer exercising oversight; they are performing an executive function. The Constitution forbids this—not to weaken Congress, but to protect both democracy and human dignity.

If the real goal is universal health care, there is a better and more honorable path. Medical assistance can—and should—be delivered rules-based, through PhilHealth and DOH hospitals, without political mediation. The sick should receive care because they are sick, not because they know someone. Students should receive support because they qualify, not because they were endorsed. Farmers should receive aid because of need and merit, not because of political allegiance. When institutions work, the poor do not have to beg; they simply apply—and are served.

Instead, what we are witnessing is the entrenchment of “soft pork” in health and social services, even as education budgets are constrained and institutional solutions weakened. This is not social protection. This is patronage medicine.

To raise these concerns is not to be “anti-legislator.” On the contrary, it is to appeal to the highest ideals of public service. True leadership does not thrive on gratitude extracted from desperation. It is measured by the strength of institutions left behind—institutions that work even when no politician is watching.

So, I end with a respectful but urgent appeal to you, honorable legislators of Congress and Senate: renounce pork once and for all—not only its old, blatant forms, but also its newer, softer, and more seductive versions. Choose to be remembered not as patrons of the poor, but as builders of just and durable systems. Restore dignity where it has been quietly eroded. Let compassion flow through institutions, not personalities.

The poor do not need benefactors. They need justice.